They don’t say ‘turn the lights off’ at Innogy’s Czech regional headquarters. With Philips tunable LED luminaires, it’s the opposite, MARK HALPER discovers.

Things have a way of getting old.

Take, for example, the Czech regional headquarters of German energy company Innogy in Prague. When it opened in 1993, it was a model of modern office facilities. Although from the outside it has managed to keep its looks reasonably well, inside, it was another matter (Fig. 1).

"For twenty years, we did nothing," explained Tomáš Michna, senior manager for facility and services at Innogy Czech Republic. "It was very dark with the closed offices, and people were not communicating with each other. The lighting conditions and cooling and heating systems were old, so it was very difficult to manage the building from a facilities point of view."

FIG. 1. The deep renovation at Innogy headquarters left the building’s outside untouched but completely changed the lighting and layout on the inside. Image credit: All images, Philips Lighting.

That all started to change in 2015 as Innogy — then called RWE — began a deep internal renovation, with lighting prioritized on the agenda along with other facility systems such as heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC).

Fast-forward to November 2017, when Innogy and Philips Lighting had turned the six-story, 108,000-ft2 building into an exemplar of modern human-centric lighting, where some 2000 LED luminaires and downlights change brightness and color temperature throughout the day to help boost the morale and circadian cycles of more than 500 employees on site.

The scheme includes a jarring dose of cold bright light first thing in the morning and various fluctuations throughout the day, such as another jolt after lunch. Czech construction company Bak also tore down internal walls, opening up space for light to travel — including artificial light as well as natural light from the unchanged exterior windows. The inside has been transformed from traditional closed offices to contemporary open-plan areas with work islands, collaborative and creative spaces, and a restaurant, with artificial and natural light informing all of it.

The results have been positively received by the majority ofemployees.

"Eighty percent of the people really like it, because the light inside the building matches more with the light outside," said Michna. "They feel aligned with the outside world, rather than feeling like being inside a building. The second thing they like is they say that after lunch, when they get tired, and the lights change colors and are more bright, it helps them to start for the afternoon sessions. And after lunch, there are usually a lot of important meetings or a lot of important tasks, and the light helps them to activate themselves, bringing more energy. Fulfillment of the tasks is better than it was before."

First, let’s quickly review human-centric lighting, which also goes by the terms "circadian lighting," "biological lighting," and "lighting for health and wellbeing," which LEDs Magazine has written about often. The general concept is that humans have been conditioned by millions of years under the sun to wake up to light that is brighter and bluer/colder during the alert hours of daytime, and which gives way to dimmer levels and amber/warmer hues toward more relaxing nighttime hours.

The science of circadian lighting is still young, and experts disagree over exactly which intensities and which hues should be used for specific hours, individuals, and tasks. But as LEDs has written, many offices are now giving it a go, applying a variety of schemes.

At the Innogy building in Prague, Philips has programmed the lighting to be at its most "alert" state first thing in the morning, when Philips likens the lighting effect to caffeine.

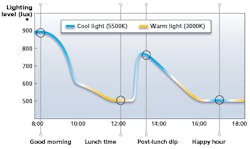

FIG. 2. The day starts with a jolt of bright, cold 5500K-CCT light at 9 a.m., then gradually dims and dips to warm before lunch. It gets jarring again after lunch, before dimming and warming but eventually going cold again at "happy hour," without brightening. The numbers to the left are light levels in lux units; a blue line indicates a cooler CCT and yellow indicates warm.

"We’ve taken our knowledge of how light physiologically benefits people from successful projects in hospitals and schools and applied it to the offices space," said Jirˇí Tourek, Czech Republic country manager for Philips. "We know that exposure to a certain comfortable bright light setting for one hour can provide a mild energy stimulus similar to a cup of coffee and supports wakefulness. Similarly, other light settings can aid relaxation or help people to wind down before lunch or going home."

When employees start the workday at 9 AM, the Philips system gets them going with a blast of 900-lx brightness tuned to 5500K — a decidedly bright and cool combination. From there, intensity gradually dips and the color temperature warms up (Fig. 2). By the noon lunch break, brightness has calmed down to 500 lx and CCT has risen to a warmer 3000K. A little bit before 2 PM, things get intense again, rising to just under 800 lx and nearly 5000K. It’s not quite as eye-opening as in the morning, but Philips considers it the correct level for offsetting post-lunch drowsiness. By 4 p.m., the lighting quiets down again to the pre-lunch setting of 500 lx and 3000K, before a "happy hour," when intensity remains low at 500 lx, but the CCT shoots up again into the cool zone.

As Michna noted, an early survey of staff showed that 80% of employees like the digitally-tunedillumination.

But what about the other 20%? "They are more sensitive to the lights," acknowledged Michna. "They don’t like the strength of the lights after lunch. It disturbs them more than helps them. They like to work in different lightconditions."

That does not mean that they have to simply grin and bear it. "Those people normally change rooms — they can go to a different room or a different working position," says Michna. They can also stay where they are.

Whether they move or stay put, they can manually override the centrally-programmed settings with a wall-mounted Philips Antumbra control "and adjust the lights according to their needs," he noted.

It’s not a perfectly individualized situation. Each panel controls lights in workstation areas that can consist of four to six employees. Provided enough employees are in agreement (LEDs did not uncover any examples of fisticuffs by the Antumbra!), then they can change settings to the group’s needs.

The Philips system works through wired technology using DALI (digital addressable lighting interface) controls. There are no wireless aspects to the system. (Wireless schemes such as Bluetooth Mesh are beginning to come into their own in smart lighting.)

FIG. 3. The human-centric lighting scheme includes window blinds tied into the control system to help deliver the correct balance of natural and artificial light.

Given that the deep renovation required a lot of rewiring, Innogy had considered another wired approach: Power over Ethernet (PoE), which routes both low-voltage electricity (LEDs require only low voltages) and data over the Ethernet cables that typically tie together office networks. But according to Michna, PoE was too expensive several years ago, when vendors quoted prices 30–40% above the Philips DALI system. Philips, itself a PoE provider, did not bid on a PoE approach at the time.

Neither Philips nor Innogy would reveal the price of the lighting overhaul, which included a mix of Philips products. Inventory included 860 Philips PowerBalance tunable-white ceiling fixtures; 96 Philips LuxSpace tunable-white downlights; 74 TrueLine luminaires; 600 GreenSpace downlights; approximately 250 Philips CoreLine downlights; and approximately 100 modularluminaires.

Philips also furnished a Dynalite control system and the Antumbra wall-mounted boxes. In addition, it provided window blinds to help with natural lighting, controlled by Dynalite to keep natural and artificial light levels in balance (Fig. 3). The Philips gear and operations are covered by a five-year support and maintenance contract.

The building renovation included a new HVAC system, overseen by a division of Innogy, subcontracting to Swiss HVAC specialist Sauter. Bak carried out the general contracting work, and another Czech company, Edifice, handled the projectmanagement.

The deep renovation had plenty of challenges. "The major complication was [that] it was a 20-year-old building, and there were a lot wires in the building when we uncovered the ceiling," recalled Michna. "We were not sure which wires led where, and which supplied electricity and data. So this was the most difficult point — not to cut the rest of the building from power and data supply."

Another complication: It wasn’t easy staging the renovation in phases while trying to keep at least most of the employees on site. "We had three phases of the reconstruction, and for each of the phases, [people in] part of the building had to be moved elsewhere," Michna said. "We increased the number of places in other parts of the building, making it less comfortable for that period of time. And some employees moved to other rented premises in another part of Prague."

And then there was that inevitability familiar to anyone who has renovated a building: "Noise was a challenge," said Michna, noting that work often had to take place at night and on the weekends to mitigate the effect.

With such expansive coverage — the one building spans five distinct connected sections, which are buildings in their own right, all adding up to what Philips says is one of the largest human-centric lighting deployments in Europe — Philips and Innogy experienced a few moments of truth when it came time to switch on the lights into full-timeoperation.

"The renovation of the existing building was undertaken in phases, which presented some challenges when installing and commissioning the lighting and its management system," said Boris Zupancˇicˇ, Philips’ Central and Eastern European development team head. "It was overcome by good architectural design, meticulous planning, and diligent execution. We were also responsible for delivering the lighting system integrated with HVAC and automated window blinds that adjust in real time to external weather conditions. The definition and fine tuning of the lighting — adjustment of the light intensity and color temperature — had to take these factors into account as well as matching people’s routine and performance curve."

FIG. 4. The human-centric lighting is in full swing all around the interior, such as in the conference area, the front lobby, by the elevator, and others.

Innogy’s Michna had a similar recollection. "After the installation, we had to take a few weeks before we tuned up the system, and because each building has different light conditions, and the light shines on it in a different way during the year, you still have to adjust the whole system during the year," he noted.

Actual installation began in April 2016. Employees had settled in fully by July 2017. But as Michna noted, it took until November to sort out the kinks on all aspects of the renovation, not just the lighting.

In fact, the settings are still in flux as the year goes on. "The first year is like a reference year," Michna said. "The cooperation with Philips is still ongoing. The installation hasn’t finished. They still have to work on that and tune it up for a year."

All the finer adjustments aside, it’s been so far, so good. Not only do employees approve of the new lighting, but according to Michna, productivity even seems to be improving. He points out that some 500 Prague employees are now doing the same job as 600 were (with the renovation, Innogy combined workers from another Prague location, some of whom transferred elsewhere in the country). The uptick is not all related to lighting — the work environment has improved in many aspects and the opening of walls has fostered communication. However, Michna believes the new lighting throughout the facilities has been a solid contributor (Fig. 4).

The installation has also delivered another benefit: energy savings. Not only are the LEDs more energy efficient than the former fluorescent lights, but they house about 150 occupancy sensors that switch the lights off in a room or area when it is vacated, saving electricity. Philips says the electric bill has fallen by around 50%.

With all the benefits, the human-centric lighting has turned an old admonition on its head.

"Before, we use to say to people, ‘Please turn off the lights so you save energy,’ so they were sitting in dark offices," notes Michna. "Now, the sun’s outside, and the lights are on in the whole office, because people believe it helps to make a more positive atmosphere. So we are not forcing them to turn off the lights to save energy. We’re letting them turn on the lights and increaseproductivity."

That’s one heck of a new message. No telling when it might get old.

Get more in-depth, in-person education on human-centric lighting at our upcoming Lighting for Health and Wellbeing Conferences. Visit lightingforhealthandwellbeing.com for program information.