Back in the spring, we reported that the US Department of Energy (DOE) had announced the launch of a new L-Prize initiative seeking to spur innovation in solid-state lighting (SSL) systems for commercial buildings. We have since learned more about the new initiative in terms of how it will be organized, the goals of the new program, and the chronology of the reprisal. Ultimately, the DOE will pay out as much as $12.2M (million) to participants over three phases. This time around, success will be tied to far more than efficacy and reliability and include factors such as connectivity and controls. Moreover, partnerships and collaboration will be encouraged.

The new L-Prize program is indeed structured far differently than was the original program launched over a decade ago. The original program was open ended with participants challenged to deliver a commercially-viable, LED-based replacement lamp that could meet a stringent set of efficacy, lumen output, light quality, and reliability requirements. That original program was arguably intended to validate SSL as a technology that would usurp legacy sources.

No-compromise SSL

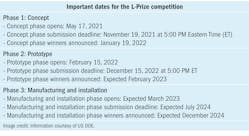

The new program will be more focused on no compromises, providing great energy efficiency and also sustainable features and usable controls. It will comprise three phases where entrants first submit concepts. Then entrants will develop prototypes in phase 2. In phase 3, participants will address manufacturing and installation of SSL systems. The program is decidedly not open ended this time around. The nearby table defines the chronology that started this past May and that will end with winners announced at the end of 2024. As with the original program, participants will work to improve efficacy, quality, and lifetime. But the new program will be decidedly systems oriented and focused on commercial installations where energy savings have the most impact and where controls can be most useful.

The systems-level emphasis implies SSL controls and most likely connected luminaires. Moreover, there is no preconceived notion of form factor or material. The one place where the original and the reprisal concur is that the winners of the competition must be manufacturable and installable for the broad lighting industry. In phase 1, the DOE will award as many as ten $20,000 prizes for concepts. Then as many as three entrants will share $2M in phase 2. And as many as two ultimate winners will share $10M at the close of the competition. The LED-centric competition encourages entrants to improve and evolve SSL systems in areas of efficacy, quality of light, connectivity, lifecycle, and innovation/inclusion.

Philips wins

Long-term participants in the LED and SSL sectors will of course remember the original L-Prize, but frankly it took place so long ago that many newcomers may have missed what was a landmark market transformation program. The Bright Tomorrow Lighting Prize (L-Prize) was conceived and launched in 2008 to accelerate development of LED-based replacement lamps that met extraordinarily-stringent performance and lifetime goals in the early SSL era when products often fell short of specification and failed prematurely. Philips Electronics (really a combination of what is now separate Philips, Signify, and Lumileds organizations) was the first company to officially enter the competition for a 60W-replacement lamp in 2009. The competition included that A-lamp category and originally included a PAR38 competition as well.

There were subsequent entrants into the A-lamp competition including from GE Lighting and Lighting Science Group. But Philips had a significant lead in the development. Philips was declared the A-lamp winner in August 2011 and ultimately collected a $10M prize. At the time the lamp sold for around $50, but it delivered handsomely on the design goals. In 2015, the DOE said after 40,000 hours of testing of 31 lamps, lumen maintenance remained over 95%.

We published an interview with Jim Brodrick, longtime director of the DOE SSL program but now retired, in the month after the prize was awarded. The lamp had already undergone 18 months of testing and Brodrick said the lessons learned in the L-Prize program would be applied throughout the SSL industry. Brodrick was correct even within Philips Lighting. The L-Prize winner was truly over engineered and had a relatively short availability window on store shelves. But elements of the design such as the iconic shape last still to this day, for instance, in Signify Hue products. Alas, the PAR38 competition was suspended in 2014 because the efficacy levels set by the DOE simply were not achievable.

Blank sheet of paper

As mentioned earlier, the new version of the L-Prize targeted at commercial buildings is far less defined. There is no preconceived notion of a product form factor or required performance levels. The DOE has said that the luminaires must be suitable for service in commercial buildings across applications including offices, healthcare facilities, educational facilities, and similar settings. Essentially, the contestants will be asked to replace the linear lighting and troffers that are ubiquitous in commercial spaces.

The DOE has made it clear that the program is a no-compromise endeavor. In other words, entrants will be expected to deliver excellent color rendering without any efficacy penalty. Flicker will be unacceptable. The DOE has said that it believes a doubling in luminaire-level efficacy is possible through improvements across the luminaire architecture including optics, driver electronics, LED materials, and more.

Moreover, participants will be challenged on two additional vectors. One is inclusion of connectivity and controls. The DOE clearly expects controls as a baseline feature that increases system-level operational efficiency. But the expectation goes further. The rules mention tunable spectrum for lighting for health benefits. Furthermore, it mentions integration with automated building systems. The DOE refers to some features as non-energy benefits — for instance, with tunable spectrum or applications such as indoor positioning.

Sustainability and end of life

The other important vector is perhaps more logistical in nature although potentially a huge technology development challenge. The DOE expects the participants to add features such as replaceable modules and yield luminaires that have sustainable end-of-life options. The winners will also be expected to be manufacturable in the US with significant enabling components coming from US manufacturers.

The phases of the competition will also be unique in the L-Prize reprisal relative to most multiphase competitions. The three phases will be independent. An entrant will not be required to compete in phase 1 to subsequently compete in phase 2, although surely many entrants will surely do so.

An expert review panel will judge each phase of the competition. The DOE has posted a PDF with rules that bound the program (downloadable at https://bit.ly/2VZOGuk). The judging panel will award points as defined in the rules with entries receiving consideration across logistic and actual performance categories. Remember, lifecycle cost and sustainability will come into play. And performance categories such as connectivity have a long list of what the rules document calls topics with each being able to earn points — for instance, reporting of energy usage. The program will be administered by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory with technical assistance from Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL).

The other key difference for this L-Prize is the option of collaboration. Especially during the prototyping in phase 2, entrants can search for potential manufacturing or installation partners. The DOE plans to aid that process by keeping an updated list of potential partners available at all times on the contest site. Specifically, the DOE said it will “connect researchers and product developers with manufacturing partners, contractors, utilities, energy service companies, and others interested in production and installation of lighting systems meeting the L-Prize requirements.”

The new L-Prize is off to a fast start. There were 14 teams already registered as of mid-August.

LEDs Magazine chief editor MAURY WRIGHT is an electronics engineer turned technology journalist, who has focused specifically on the LED & Lighting industry for the past decade.