Holland’s largest supermarket chain, Albert Heijn, has just wrapped up a 12-week trial of lighting-based indoor positioning systems (IPS) at a single store near Amsterdam. By all accounts, including the retailer’s, the pilot went remarkably well.

But whether the venerable Dutch retailer rolls out the system across multiple locations is no certain thing. As of this writing, the Zaandam-based company, part of the €62.9 billion ($79.3B) Ahold Delhaize global food group, was deliberating whether to take even the next small step, in which it would sample the Signify-supplied system in another 5–10 locations, a small fraction of its 884 sites in the Netherlands.

Among Albert Heijn’s concerns are cost, return on investment, and the possibility that it could procure similar technologies from outside the lighting industry.

Welcome to the long gestating Great Light Hope known as IPS. Lighting vendors have high aspirations for embedding information technology (IT) into commercial lights and luminaires that would communicate with in-store shoppers’ smartphones, guiding people around cavernous retail aisles straight to the items on their shopping lists.

Such smart lights will link into consumers’ loyalty schemes and personal profiles, and will offer personalized discounts and product suggestions. Everyone wins. The shopper enjoys a positive and affordable experience, and the store gains sales and customer satisfaction.

IPS is a big arrow in the lighting industry’s Internet of Things (IoT) quiver aimed at making lights intelligent data gatherers and disseminators, and tying them into cloud computing systems that analyze customer trends. But one of the most notable things about IPS, other than its potential, is its prolonged proving period.

Lighting vendors have been talking about IPS in earnest for a good six years now, possibly longer. GE, in an earlier incarnation of the industrial company, appointed an executive in charge of indoor positioning at least as far back as 2013, and was posting promotional IPS videos at around the same time. Signify, then called Philips Lighting, launched a pilot IPS trial with a Dutch museum in 2014, and soon afterwards it outfitted a single Carrefour store in Lille, France.

Other lighting vendors have had similar timelines. But except for one publicly known exception — the Target retail chain in North America, which in the past year-and-a-half is believed to have built lighting-based IPS from Acuity into well over half of its 1850 stores — lighting suppliers have to date fallen way short of large-scale chainwide deployments (although there are whispers that Walmart has some IPS in the lights).

Rather, they have settled for a number of one-off implementations. To name a few: Signify has an Edeka store in Dusseldorf, Germany, an aswaaq store in Dubai, and a couple of Media Markt electronics shops in the Netherlands. Osram outfitted a separate Edeka in Berlin late last year, although it did manage to get into 23 Swiss fashion shops in a curious non-lighting deployment. And Zumtobel has an E.Leclerc store in Langon, France.

Business process change

The examples are indeed slowly building, but in the big picture it’s all just a sliver of where the industry had hoped to be by now.

Yet most of these lighting vendors still believe, as they have for the last several years, that large-scale, lighting-based IPS deployment is just around the corner.

“IoT is a business process change, it’s not a technology,” said Tomasz Zareba, the new director of digital services at Zumtobel — a modern-day lighting job title if there ever was one — in explaining one reason why IPS adoption has taken so long.

Zareba is the former director of European IoT for telecom giant Nokia. Dornbirn, Austria-based Zumtobel hired him in October to infuse an IoT spirit into the company, a mission which he is taking to heart.

“The lighting industry is an important innovation bearer in the IoT domain, and a strong enabler for indoor IoT use cases,” said Zareba. He was adamant that the time has come for lighting-based indoor positioning, with all of its targeted, personalized marketing and sales capabilities, to help retailers thrive in a world where Amazon’s threat grows constantly more pervasive, especially now that it is opening its own high-tech physical stores.

In an effort to build out a common VLC habitat, Signify has licensed 22 OEMs — including Signify’s own Philips brand — to make VLC-enabled lights. Between them, they offer 47 different VLC luminaires and 23 brands.

Signify is equally bullish, and has been for some time. One of the main reasons for its perennial optimism is that it has already made the significant headway of landing IPS-equipped lights in 3 million m2 (about 32.3 million ft2) of retail space. Some of the lights are Signify’s. Some of them are licensees, of which Signify has 23 (as of this publication). The lights are a big first part of the equation, as they are the infrastructure for an IPS system.

But what’s missing across most of the installations is all the rest of the stuff that turns the backbone from dormant into operational: software and live IT connections. The LED lights do what lights have forever done — they illuminate — but their IPS has not been connected and switched on.

It’s the navigation, stupid

The small minority of locations that have switched on the IPS have provided valuable learning experiences for Signify. According to Simon den Uijl, head of partners and ecosystem indoor positioning, in a finding that other vendors would dispute, the main use of IPS for shoppers is wayfinding — locating products.

Aren’t they also using it to receive targeted discounts and promotions, as Zumtobel and Acuity would contend?

“I do like that idea, but I don’t see much of it,” said den Uijl. “Somehow, it’s all geared to indoor navigation.”

Certainly, indoor navigation was the star of the show at Albert Heijn’s recently completed September-to-December trial in Hoofddorp, about 10 miles southwest of Amsterdam. In fact, it was the only part of the show, as the store offered no other capabilities but wanted to gauge shoppers’ level of interest in a location app that Signify developed for the retailer.

On that basis, the implementation was a roaring success.

“We saw a high level of satisfaction from the user base,” said Albert Heijn’s Steven de Kroes, who in his role as format developer helps create store designs and processes. “They were able to find products quicker than they would otherwise do by asking an employee or finding it by themselves.”

This Albert Heijn shopper found eggs via her Signify IPS app. But now she has to balance them in one hand while holding her VLC-connected phone in the other. (Photo credit: Signify.)

The customers’ thumbs-up was evident in other ways, as about 1000 shoppers downloaded the app, even though Albert Heijn barely promoted it. It was a large number for the 1400m2 (about 15,000-ft2) store.

“It exceeded our expectations,” said de Kroes. “And we saw, on average, people came back to use the app. That told us we were moving in the right direction. Just for the functionality of finding products, people were coming back to use it.”

Or maybe it’s not the navigation

While the trial boded well for navigation purposes, navigation does not necessarily lead to a quantifiable increase in sales. So Albert Heijn will be evaluating the cost of the system versus the payback.

“We are now in the middle of the decision process on whether to go further,” de Kroes said, noting the retailer could decide by sometime in March. “The next step would not be a nationwide rollout but a bigger form of testing in more stores — typically between five and ten stores — and more use cases.”

The additional use cases would entail integrating the IPS system into Albert Heijn’s own existing customer app, and supporting functions such as targeted sales offers. And the additional stores would also involve lighting overhauls. At Hoofddorp, the timing was good because the store was going through a major remodeling including lighting.

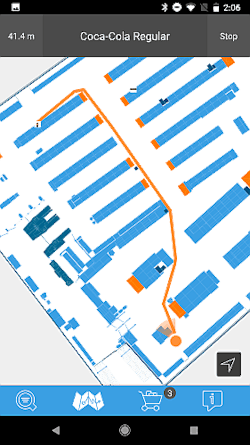

In a rush for your Coke? This simple Signify map takes you right to it. (Photo credit: Signify.)

“The technology itself, it’s quite a cost,” said de Kroes. “And then there’s the capex of lighting. The hardware, the installation, application development, the partnering up with software companies. If you were to add it all up, it’s quite an amount. So if the use case is just helping people find products, in the long run it probably won’t add up. We’ll have to look into other types of use cases.”

One of de Kroes’ concerns is that shoppers in wider trials might balk at using what den Uijl says is Signify’s preferred technology, visible light communications (VLC). VLC works by embedding data in lightwaves emitted by a store’s ceiling LEDs. It is a highly accurate technology; it can pinpoint a product to within 30 cm, compared to 2–3m for Bluetooth radio beacons that some lighting vendors are embedding in luminaires.

Zumtobel has been trialing lighting-based Bluetooth IPS at an E.Leclerc store in Langon, France for a little over a year, after first announcing it two years ago. The store has noticed increased sales but has not rolled out IPS to additional locations yet. (Photo credit: Zumtobel.)

Whereas smartphone users in general are accustomed to freely connecting their phones to Bluetooth, they can balk when directly asked for permission to access the camera that receives the modulated data from the LEDs, especially as users grow more wary over the potential for privacy invasion and data theft.

Another potential downside to VLC is that it requires the shopper to constantly have his or her phone out and pointed toward the lights.

Scanners trump phones

Perhaps those reasons explain why Signify itself has discovered that the end-user uptake in its various one-off pilots has been low. Typically, only about 5–10% of users in trials have chosen to download apps onto their phones, den Uijl said.

However, in one of the industry’s newest developments, hope has arrived in the form of in-store handheld scanners, particularly popular in Europe, that shoppers use both to self-scan items as they place them in their shopping carts and to check themselves out.

Those devices, made by Lincolnshire, IL-based Zebra Technologies, in some instances now include navigational links to Signify VLC lights, and are in use in stores in Europe which neither Zebra nor Signify would identify. The devices do not require special end-user permission, because they are not end-user property. And stores typically design them to mount on shopping carts, so by default they conveniently face the lights.

According to den Uijl, early anecdotal evidence indicates that between 30% and 60% of Zebra users are tapping the VLC-based navigation — a huge increase over the 5–10% phone uptake. Zebra is providing three different VLC-enabled models — the PS20 for consumers, and the TC52 and TC72 for staff.

“I’m quite positive that the Zebra devices are going to be a big help in waking up this sleeping beauty, and getting that 3 million square meters of installed lights activated and actually used,” den Uijl said.

As much hope as the Zebra gadgets provide, they also serve as a symbol for what is one of the most daunting challenges facing the lighting industry’s push into IPS: The Zebra products also support other IPS technologies including Bluetooth and others that retailers can procure — and have been procuring — from more traditional IT vendors, not from the lighting industry.

Whose industry is it?

“We have a team of people that for many years we’ve been working with in the location space,” said Mark Delaney, Zebra’s retail strategy lead. “Our goal is to enable as many different locationing technologies as possible for our customers. VLC is one of those. There’s over a dozen technologies that can be utilized around location, including things like Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, and Ultra-wideband.”

That observation is not lost on de Kroes at Albert Heijn, where the evaluation of whether to expand the Signify VLC trial includes looking into Bluetooth beacons that would come from a company other than Signify, probably an IT company.

It’s an observation on the mind of anyone trying to market lighting-based IPS. Whether they are advocating VLC, luminaire-embedded Bluetooth beacons, or other lighting-related technologies, as they themselves attempt to serve more IT purposes, they are vying against IT companies.

“In the end, we all compete for one use case, which is called indoor positioning,” agreed Zumtobel’s Zareba. “It can be done in different ways.”

Zareba pointed out that the lighting industry has several advantages over the non-lighting industry for Bluetooth deployment. Bluetooth beacons inside light fittings draw on electrical power that feeds the lights, and are not subject to failed batteries every two years or so, which can be difficult for stores to locate and replace.

And it often makes economic sense to add Bluetooth-enabled luminaires during a store refurbishment, which can typically include a lighting retrofit anyway, Zareba added, noting also that embedded beacons can avoid unsightliness in higher-end stores that place more of a premium on interior design.

Others in the lighting industry have pointed out yet another advantage for fitting Bluetooth beacons into the lights: The density of luminaires makes them ideal for Bluetooth location purposes versus in non-lighting Bluetooth location deployments, where beacons typically reside too far apart to be effective.

Still, the reality of competing against IT companies has prompted one lighting vendor, Osram, to on occasion provide Bluetooth beacons even where it does not provide lights, as it has done at Swiss Guess and Marc O’Polo fashion outlets.

In another technological variance, the positioning system that Osram installed at the Berlin Edeka uses powerline communications as part of its topology, running data to lights over electricity lines. Osram, which recently regrouped, declined to be interviewed for this article, noting that it is in the middle of further restructuring its IPS business.

Bluetooth versus VLC

Meanwhile, the lighting industry itself is divided over IPS technologies. Den Uijl at Signify prefers VLC for its accuracy, and also because it helps distinguish lighting’s indoor navigation proposition from the IT world’s, marking a unique way for lighting to truly “tap into this new value pocket, which is the indoor positioning market, and allow us to go ‘beyond lighting’ for customers.”

But Zumtobel’s Zareba is a staunch believer in Bluetooth. “Bluetooth is a technology with massive penetration,” he pointed out. “It’s safe to say that the majority of customers have a smartphone, and when a smartphone is present, it normally has Bluetooth.”

Zareba has little concern with Bluetooth’s accuracy compared to VLC, noting that shoppers at E.Leclerc’s Langon trial have only partially used it for navigation because 75% of the customers are recurring customers. As he put it, “They already know where the ketchup is and appreciate freedom during shopping.”

Rather, the main use at E.Leclerc has been for what he called “proximity marketing” — spotting when a user is near a favorite item and pinging an offer to the phone for that item. The Bluetooth system allows for proximity-based messaging near the customer’s favorites because customers can agree to link to their loyalty program.

On Target

And again, VLC systems might run into resistance from users not agreeing to give access to their cameras. That is something that is believed to have stalled VLC uptake at Target — where the lights at many stores are said to be equipped with both VLC and Bluetooth, but where only the Bluetooth is currently switched on.

Acuity, which has long been believed to be the IPS provider — neither Acuity nor Target has ever confirmed that — told LEDs Magazine that its Bluetooth and VLC equipped lights are now present in more than 300 million ft2 of retail space in North America, which represents a whopping increase over the 50 million ft2 reported less than two years ago when about 100 Target stores were active. Later that year, Target decided to widely roll out lighting-based IPS in more than half of its 1850 stores by Christmas. LEDs asked Target for an update but did not receive one in time for this article.

Target is one of the few known examples of a retail chain that has widely rolled out lighting-based indoor-positioning systems, engaging shoppers with discounts and information on items such as food and apparel, and also providing stores with marketing and merchandising analytics based on their movements. Target has outfitted lights with both Bluetooth and VLC but is currently using only Bluetooth. (Photo credit: Target.)

Of the 300 million ft2 of retail space Acuity cites, about 150 million ft2 is activated, engaging shoppers and providing stores with marketing and merchandising analytics based on shopper movements, according to Greg Carter, Acuity’s senior vice president of connected buildings technology. Acuity has also started piloting analytics that examine the efficiency of employees and of processes such as moving goods from storerooms to shelves.

It’s all tied into an ecosystem that Acuity calls Atrius, aimed at establishing IT partnerships with hardware, software, and data companies that can turn lighting networks into veritable IT networks. Other vendors have similar integration programs, such as Osram’s Lightelligence initiative and Signify’s Interact platform. And vendors are endeavoring to put IPS to work as asset trackers — locating wandering medical equipment in hospitals, or shopping carts in stores, for example.

For all of the industry’s efforts going back a good six years, vendors have yet to turn lighting-based indoor positioning into a mainstream technology among retailers and other commercial users. But they are convinced they are moving in the right direction. Like many great mapping expeditions, this one is taking a while.

MARK HALPER is a contributing editor for LEDs Magazine, and an energy, technology, and business journalist ([email protected]).