This article was published in the April/May 2012 issue of LEDs Magazine.

View the Table of Contents and download the PDF file of the complete April/May 2012 issue, or view the E-zine version in your browser.

+++++

The sixth-annual LEDucation conference and exposition was held in New York, NY, in March. The conference portion of the event provided attendees with a chance to better understand the ways that LED lighting enhances high-end retail environments.

Where no light has gone before

A panel discussion, headed up by Nelson Jenkins, a lighting designer with Lumen Architecture of New York, NY, explored the advantages that only LED lighting can bring to luxury retail applications. These include an improved aesthetic and the ability to take advantage of new form factors.

For instance, in a façade lighting project that Barteluce Architects performed for Dior on 57th Avenue in New York, Sean Hennessy, who currently leads Hennessy Design, said “LEDs allow us to bring light to places we haven’t previously been able to light; it’s a more versatile avenue.” In designing the Dior façade (Fig. 1), Hennessy stated that the need for a high light intensity of 3500 lux combined with the shallow depth of the store front made LEDs the best choice. He stated that halogen lighting created too much heat in one concentrated spot, while fluorescent lighting consumed too much space. With LEDs, the space occupied by the lighting was pencil thin.

“We created Dior’s signature ‘cannage’ pattern using four panels of either glass or acrylic, one panel with a dot pattern and another with vertical, horizontal and 45° lines. The combined effect is that of an optical illusion as the observer walks past the store,” said Hennessy. The color temperature for the project was 5300K, accomplished using individual LEDs at 5200K and a color-correcting film on a panel. He said they evaluated seven LED products and settled on an edge-lit LED approach using over 450 LitePads from Rosco (13.5×12-inch). He added that they situated the LED drivers for easy access for maintenance, followed by the wiring, the LED LitePads and the panels. The entire system consumes 12,000W.

Next in the retail panel, Ruth Mellergaard, an interior designer with Grid/3 International in New York, NY, talked about the implementation of advanced lighting in jewelry stores. She said that before energy-saving lighting technology, jewelry stores typically consumed 7-9 W/ft2, which dropped to 3-5 W/ft2 when halogen lamps were brought in. Now, with LED lighting, 1.2 W/ft2 or less can be achieved.

Mellergaard emphasized that color temperature is a huge issue when it comes to lighting jewelry with LEDs. “We have found that many vendors are pushing high color temperatures, in the 6000-8000K range, because it makes the diamonds look better.” She said the downside to this approach is that a person’s skin will not necessarily look realistic at these high color temperatures and the chosen jewelry will look different when the person leaves the store.

Another early issue with LEDs was the glare from unshielded LEDs. “Jewelers had a tendency to choose very bright light and to illuminate from the rear of the cases, particularly with early installations, so glare was a problem,” said Mellergaard. Glare is now managed by positioning the LED strip lights on the front of the display cases. “In some instances, companies will add a color-corrected fluorescent light to the rear of the case, but that approach increases the cost,” said Mellergaard.

Mellergaard highlighted one of the most significant upsides to using LEDs. She said that jewels tend to “wink” under LEDs, a glittering effect that is not accomplished with any other light source.

The other key advantage is energy savings. “Some jewelers are used to running their air conditioning year-round to compensate for the heat from metal-halide lighting,” said Mellergaard. With LEDs, the energy savings from the lighting and air conditioning combined are significant. However, Hennessy stated that in his experience, depending on the project, there could be little or no energy savings associated with LED lighting. “But the quality of the light is such that you become convinced it is the best solution,” he said.

Renee Cooley, principal of Cooley Monsanto Studio (CoMoS) in New York, NY, agreed that LED lighting is not necessarily used throughout a luxury retail establishment: often the lighting solution is a combination of different types depending on the need. She described a lighting installation in a Tiffany & Co. store in New York, one that contains a private room where the most expensive jewelry is tried on. This room has a large mirror with LED strip lighting around its periphery that uses three color temperatures, 4000K, 3200K and 2800K. By alternating the light, customers can test the jewelry under different conditions. “We are trying to persuade our cosmetics clients to consider this technology as well, but they haven’t taken us up on it yet,” said Cooley.

When the panelists were asked whether they tended to use the same LED products from the same vendors from one project to another, both Cooley and Mellergaard responded that yes, such was the case. “When you find something that works well, you stick with it,” said Mellergaard.

Product consistency

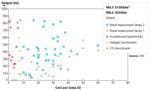

Product consistency was a topic that arose a few times during the course of the day, as Naomi Miller of the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) discussed. Miller, a former lighting designer, knows well the challenges that designers face in choosing LED lighting products that will perform as advertised. In fact, she reviewed recent study results from the DOE’s Caliper program in her presentation, which has indicated dramatic increases in LED lamp performance, yet still a broad spread in performance among products tested. For instance, the DOE recently published the second report on retail replacement lamps, which involved the testing of 38 lamps from 18 manufacturers and 9 retailers. Lumen output (Fig. 3) varied by product but exceeded 800 lm in some cases.

The average price per kilolumen of the collection of retail replacement lamps dropped from $139/klm to $63/klm between the LED lamps purchased in November 2011 and the lamps in the first study, purchased in July and August of 2010. In terms of efficacy, eleven A19 LED lamps achieved a mean efficacy of 60 lm/W in round 2, while the first-round products featured a broad spread with some A19 lamps performing as low as 20 lm/W.

Energy Star update, new specifications

Beyond the anonymous testing of products that the DOE performs, consumers rely heavily on the Energy Star label. At the conference, Alex Baker, Energy Star lighting program manager, provided recent updates to the program. As Baker explained, Energy Star is a third-party certification program based on ISO standards. Testing labs and certification bodies (CBs) must be EPA recognized. To date, there are more than 40 recognized testing labs for lighting worldwide and 8 certification bodies (CBs) in the US. Baker said that when Energy Star specifications for luminaires and integral lamps are updated, products are not grandfathered in. All qualified Energy Star products must meet the existing current specifications on the date of manufacture.

Baker talked about the fact that the effective date of the Energy Star Luminaires V1.1 specification, April 1, was just around the corner. As of April 1, if a luminaire that was qualified to the previous Energy Star spec has not been certified by a recognized CB to the new specification, it can no longer carry the Energy Star label.

The Luminaires specification combines two specs for Residential Light Fixtures (V4.2) and Solid State Lighting Luminaires (V1.3) to form a technology-neutral set of performance requirements. In a similar fashion, the specifications for Integral LED Lamps (V1.4) and Compact Fluorescent Lamps (V4.3) are being combined into the Energy Star Lamps V1.0 specification, which is expected to be finalized this year and will go into effect in 2013.

Baker also talked about the publication of IES’s LM-82 standard, which had occurred the week prior to LEDucation. The new standard provides the approved method for “Characterization of LED Light Engines and LED Lamps for Electrical and Photometric Properties as a Function of Temperature.” LM-82 is designed to establish consistent methods of testing and reporting the performance of LED light engines and integrated LED lamps at room and elevated temperatures. LM-82 reports will assist luminaire manufacturers in selecting LED light engines and integrated LED lamps for their products, particularly decorative luminaires like chandeliers which cannot be easily measured with LM-79.

Digital lighting, drivers and controls

Chad Stalker, regional marketing manager of Philips Lumileds in San Jose, CA, presented a talk about LED lighting and the digital world. He acknowledged that while LEDs are, of course, digital, it is the movement of the entire lighting industry to a digital infrastructure that is significant on a broader scale. Stalker commented that some LED lighting users have stated that LED lighting actually requires 4X the effort to install as previous lighting systems. He stated that the industry needs to solve key control and connectivity issues in order to fuel widespread adoption of LED lighting.

This talk provided a good basis for the evening’s panel session on controlling LEDs. The overall problem that a panel of experts took on was the fact that the lighting design community has been led to believe that LED lighting can be easily dimmed and controlled. However, with the increasing number of products offered, driver and control incompatibilities have occurred and installations have not gone as smoothly as anticipated.

The panel was led by Craig Fox, northeast architectural regional manager of ETL Architectural and included Gilles Abrahamse, president of eldoLED America, based in San Jose, CA, Sleiman Zogheib of Redwood Systems, Gabe Gulliams, a lighting designer with Buro Happold in New York, NY, John Gebbie, systems division manager of Barbizon Lighting Company in New York, NY and Ethan Biery, design and development leader at Lutron in Coopersburg, PA.

Biery started out by saying that knowing that a product is capable of dimming doesn’t mean much. He said a user needs to know how rapidly the controls dim the light and what the minimum level looks like. “Only then will you know if the product can meet your needs.” When asked why the driver and dimmer compatibility issues are so complicated today, Biery stated that relative to fluorescent lighting, when there were a handful of ballast manufacturers, today there are perhaps a thousand LED driver manufacturers, and some have little or no lighting background. He said “often products do not perform as expected due to a lack of preparation.”

Abrahamse added that “controls standards do exist; however, they are interpreted differently among manufacturers, which is the reason that compatibility testing must be done properly.” Another panel member, Sleiman Zogheib of Redwood Systems said that while standards exist for dimmers, standards do not exist on the LED board side.

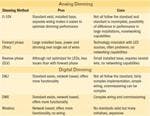

Table 1 summarizes some of the attributes and drawbacks to using various control methods, including whether standards exist and the complexity of wiring and implementation. A significant benefit of any digital approach (DMX, DALI, wireless) is the ability to network the control system, especially for large installations.

Compatibility testing between dimmers and drivers is an inevitability for LED designs as the panelists discussed. However, on a given project sometimes it is not clear which party is responsible for compatibility testing. Gebbie, who specializes in systems integration, stated that when a lighting control systems integrator is involved, that person is responsible for compatibility testing. However, often with projects of limited size or scope, this person is not present and compatibility testing can become a shared responsibility between the electrical contractor and the suppliers of the lighting systems, drivers and control systems.

Gebbie suggested that whichever component is purchased first for a project, either the controls or driver, will limit what can be purchased in terms of compatibility. Biery commented that some luminaire manufacturers will provide information regarding which controls and drivers were used in the testing of their luminaires, which is terrifically useful. However, often, the onus is on the user to obtain these details.

Regarding the future of control options, Zogheib pulled out an internet cable, held it up to the audience and stated that it’s time that lighting systems run like our phones and security systems -- over a communications cable.” He cited the standard for commercial buildings, the TIA/EIA-862 Building Automation Systems Cabling Standard, which includes internal and external lighting, provides for low-voltage system controls, and should be applied.

While such an approach does seem like a leap relative to current approaches, the panelists nonetheless acknowledged that intelligent building systems and architecture, coupled with compatible controls and drivers, will lead to energy-efficient, cost-effective lighting systems.

Finally, the panelists discussed the ongoing issue of flicker. They noted that while LEDs, as semiconductor devices, are simple to dim in terms of controlling the current or duty cycle passing through the LED, they are not “forgiving” because their extremely fast response time makes any disturbance on the current signal visible as flicker. Whether flicker becomes a problem also depends on whether pulse-width modulated (PWM) dimming or constant-current reduction (CCR) dimming is used.

For instance, PWM dimming works well with phosphor-converted LEDs, so there is little color shift with dimming and dimming to low levels is accommodated. However, the occurrence of flicker becomes a function of frequency and there is potential for line noise. Alternatively, CCR dimming tends to regulate poorly at low dimming levels and color is likely to shift with phosphor-converted LEDs, but noise and flicker are not typical problems.

Flicker was a concern that PNNL’s Miller also provided an update on regarding industry activities. She said that the IEEE has formed a committee (PAR1789) that is working toward developing a better flicker metric. The DOE is performing research to establish a range of waveforms from LEDs and it is discussing the addition of a flicker waveform to Caliper testing procedures. Finally, DOE members are working with various other industry committees to address the integrated performance of dimmers and LED drivers.