This article was published in the September 2011 issue of LEDs Magazine.

View the Table of Contents and download the PDF file of the complete September 2011 issue.

+++++

Bringing products to market based on new technology is a risky business. The small number of truly successful innovations contrasts with the large number of new products that have failed to realize their promise. It can be confusing to read about how advancements in LED technology are transforming the lighting industry, because that future won’t happen unless we get the innovation right. We should consider how solid-state lighting (SSL) technology companies can employ system engineering, with all critical stakeholders using better measurement, validation and communication to get the innovation right in today’s new economy.

To efficiently penetrate the market and realize its full potential, key stakeholders must play their part in building a comprehensive and accurate body of knowledge about the new product experience. This will assist the earliest customers in making informed, thoughtful and prudent decisions, and help build the market on a foundation of realized expectations.

Such a body of knowledge includes two important components. First is the technical performance of the product in real-world conditions. This includes all aspects of the whole-product performance (including the LED chips and their drivers), and encompasses energy savings and power quality; product life and maintenance; light output, color, temperature, and uniformity; dimmability and controls performance; and environmental impacts.

Second is the user benefits and real-world impact of the product. In the case of SSL, some possible impacts include: • The relative value of an entirely-new customer experience. This can only be understood through gauging consumer reaction to the in-situ experience of an activity under the new lighting conditions.

• The enhanced brand of a retail business and its attractiveness to customers, as well as enhanced real-estate value.

• Monetizing the value of improved productivity and health of employees, or of livestock in agricultural environments.

• Increased safety and security of business and municipal environments.

LED lighting represents perhaps a true opportunity for a potential technology home-run. In the March 2011 issue of LEDs Magazine, Philip Keebler of the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) demanded “show me the data” and pointed out the need for more measurement and validation of system efficacy, driver efficiency, and power quality. We agree, and call for even further data analysis that is focused on the customer.

Manufacturers as stakeholders

The market for new lighting products is competitive, and the potential rewards are high. Manufacturers must trade off the desire to be first to market with the need to provide the market with robust information about product capabilities and performance. Successful products will be focused on meeting stated and unstated customer needs. New-product-development guru Robert Cooper (www.prod-dev.com) says the inability to effectively match a new product to real-world customer needs is the most frequent reason for new product failures in America.

Getting truthful answers to the good, bad and sometimes painful side of LED lighting is critical to ultimate market success. Among the key questions are:

• What drives a consumer to pay (or not pay) for energy efficiency?

• What level of dimming provides energy savings without sacrificing perceptions of safety in outdoor lighting?

• What are the primary components of value, and what are they worth?

• Alternatively, what are the pain points with today’s lighting that will drive consumers to LEDs?

For companies intending to be in the market for the long haul, it makes good business sense to be a leader by providing decision makers with a robust body of knowledge regarding new products. Measurement and validation should include:

• Relevant customer research data

• Test data for standards and certification compliance

• Independently-verified field-performance data

• Case studies to illustrate the application and customer reaction.

Demonstrations

Outsourced Innovation has managed over 15 LED demonstrations in collaboration with Midwest utilities, ranging from outdoor street and area lighting, to on-campus university lighting, to creating LED lighting conversions in agricultural settings. Among the lessons learned from these demonstrations is that measurement and validation clarifies product performance and aligns expectations with proven performance. Also, business value beyond energy savings is just as important and needs to be evaluated, too.

A true breakthrough will not occur just because LED technology is used, but because of the added value the technology brings to enrich our lives. We need to understand and monetize that added value.

The DOE works hard to publish realistic reports from both Gateway and Caliper programs. These studies help temper the “coolness” factor surrounding the notion of digital lighting, so the marketplace won’t be disappointed with LEDs.

If there is an unforeseen problem or disappointment with SSL, the product can leave a bad impression with the public. Even if a fix is found that makes the product superior to anything else in the marketplace, the damage can be irreversible and be further exacerbated with today’s social-media tools. So understanding your customer and the complex operation of SSL systems is advisable before making one big enthusiastic sales pitch on LEDs. Municipal and commercial customers

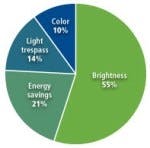

The City of Apple Valley, MN, and its host utility Dakota Electric Association surveyed residents as part of a recent demonstration project. Brightness was found to be the most important characteristic in a residential street-lighting system. Surprisingly, energy savings, light trespass and color were far less important to consumers (Fig. 1). These results suggest that, when residents view brightness as far more important than energy savings, education is needed to support the rationale for reducing light levels during after-midnight hours.

The good news is that our research consistently shows that, no matter what the geographic location, LED outdoor lighting is preferred to conventional street lighting by a factor greater than 7. But a related question for builders and home buyers is this: will an LED lighting system create a more attractive place to live, adding new value to real estate? New product research should characterize that value, as it will help justify a scalable deployment of new and more expensive technology.

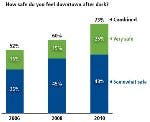

After testing several manufacturer’s products, the city chose thirty-two Capella LED fixtures from Philips. The lamps were installed on State Street and promise to deliver a 45% energy saving. The city of Bettendorf routinely tracks residents’ perception of downtown safety at night (Fig. 3). Results show a 20% increase in the city’s safety score at night following the installation of LED streetlights in 2009. Defining additional value of this type will be important in order to accelerate the technology adoption with other municipalities.

Taking it one step further, the city of Bettendorf could track whether the downtown convention center attracts more visitors or lures more booked conventions due to the installation of SSL systems. Again, this level of evaluation could help to justify such installations.

There is a growing body of evidence that customers are installing LED lighting products like light bulbs, with very little if any efforts to understand the nuances of the semiconductor technology or consideration of whether it indeed makes a good business case. But doing business without listening to the customer is like sailing a ship without a rudder: it may take a lot longer, or worse yet we may never get there.

Lighting professionals may not always understand the unique photometric characteristics of LEDs, or their optical or thermal behavior. They may not have regard for what type of LED lighting system the community prefers on the parkway in front of their homes, or whether residents may want to have less-bright streetlights or even the ability to control brightness. New innovation cannot survive on intuition alone.

These communities can be our labs. A close watch of customer insights can bring innovation to the most iconic and established products like lighting. But a lack of coordination and good data collaboration has been a big barrier to innovation in the past.

Examples from agriculture

Another critical example involves US-based agricultural businesses. What problems have evolved in such operations using today’s energy-efficient lighting systems, and what new value can be engineered into an LED system?

The National Rural Electricity Cooperative Association’s (NRECA) Cooperative Research Network, along with Oklahoma State University, has commissioned several agricultural LED field assessments to seek some answers. Early power-quality measurements suggest LED performance that is true to manufacturers’ claims, and that has matched or slightly better light levels (Table 1 and Table 2) compared with incumbent technologies. Energy savings of 50% have been validated for LED conversions in both swine and dairy facilities.

For these field studies, researchers hope to prove that the added value goes beyond energy savings. The hypothesis is that animal livestock and poultry will exhibit measureable weight gain or increased milk production, or that farmers could realize a reduction in feed costs by leveraging the spectral light intensity of LEDs. Many of today’s progressive farmers have advanced tracking systems in place to evaluate behavioral data, along with the power-usage data collected by the utility, so the full value of the new lighting system can be determined.

Robinson further commented: “We’ve gone through 3 cycles of piglets with no damage or breakage to the LED lights and that’s substantial when we typically replace many CFLs each month. That’s the real value of LEDs for our operations.”

Table 2 shows promising results from an LED dairy conversion project for about 120 milk-producing cows. However, these findings beg the question: will more LED fixtures be required or could re-engineered optics provide the additional benefit of driving a behavioral change? And especially as past research implies that 15 foot-candles are necessary to instigate an increase in milk production (Josefsson et al., 2000). The answer appears to be no, more LED fixtures may not be required: early field data at the dairy is showing a 13% increase in milk yield on the LED side of the barn, suggesting a compelling argument for LEDs. However, there is a need for continued study.

Utilities as stakeholders

Electric utilities have an important role in demonstrating significant new energy-saving products and in facilitating their adoption in applications that make good business sense. CFLs have been a pillar of utility energy-efficiency program portfolios, but now utilities are beginning to embrace SSL.

Utilities and their regulators are recognizing the importance of a comprehensive measurement and verification approach to validate the full value of SSL and ensure an apples-to-apples baseline comparison for determining energy-efficiency savings.

Outsourced Innovation recently held a workshop for MidAmerican Energy on solid-state street lighting, bringing together Iowa municipalities, manufacturers and distributors. The main take-away from the workshop was how utilities and municipalities typically don’t have the staff to select a quality LED system. Dave Ahlberg, MidAmerican Energy’s Product Manager of Industrial Energy Efficiency Programs, stated: “We want to be a good resource for our customers and advisor for SSL projects, offering grants or incentives to help prove market acceptance of the technology.”

For SSL, utilities will also need to be creative in designing new rate structures that preserve the diversity of street-lighting ownership options now offered to municipalities. Utilities like the controllability features of SSL, which allow lighting-optimization strategies for different municipal applications and have a natural fit into the industry’s vision of the “smart grid.”

Utilities strive to achieve reliable electricity service and high customer-satisfaction scores. Consumers look to their electricity provider for leadership and education on emerging technologies that save energy. Good measurement and validation provides customers with the unbiased facts on the results that new technology can deliver.

Conclusion

SSL has significant market potential, but it is still in the critical early stages of its development. Product success depends upon the market taking a system-engineering approach and evaluating the individual technology components as an integrated product that provides a variety of customers with an important and complex energy service. Market participants must also support customer decisions by tempering product claims with solid real-world test results, as well as designing products and services that provide optimal value by listening to the customer.

Manufacturers, service providers, municipalities, electric utilities and end users all have a stake in the success of SSL technology. Getting the innovation right is more important today when word of failed expectations can reach so many decision-makers very rapidly. However, we can indeed leverage SSL’s future market potential to transform lives and position the economy to move forward.