This article was published in the November/December 2011 issue of LEDs Magazine.

View the Table of Contents and download the PDF file of the complete November/December 2011 issue.

+++++

With all the attention devoted to LEDs and LED lighting, you hear surprisingly little about the rest of the electronics in LED products — what is known as the driver. Yet, the driver design determines such things as whether the product is properly loaded or inefficient, or whether the LEDs have to be tightly selected or can be loosely binned. And if you think that driver design is well understood and mature, you are wrong, for reasons that this article will discuss. Driver design is evolving rapidly to keep up with new applications and new requirements, such as improved power factor correction and sophisticated dimming for improved uniformity and reliability.

Driver IC market scales with LEDs

Let’s make one thing clear: the market for LED driver ICs – an important component of most LED drivers – is significant, at $2 billion. Also, it’s growing at about the same rate as the LED market, about 13% per year (Fig. 1).

The next big opportunity in LED drivers is in LED lighting. There have been LED lighting products in the market for many years, but in niche categories like architectural lighting, exit signs, and flashlights. Now, LED replacement bulbs are being sold in hardware stores, with the promise of large-volume sales but extreme demands are being made on size, efficiency, and cost. After that will come growth in general commercial and industrial luminaires, as building owners choose LED lighting for the lower-life-cycle cost compared to legacy lighting. The residential segment will take longer because private homeowners donate their labor for bulb replacement and do not strictly rationalize their life-cycle costs.

The driver is important, but it’s under-appreciated by the industry and difficult to forecast. Why is that? The following sections explain.

1. Confusing terminology

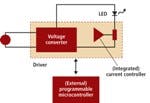

One reason is that the terminology is absurdly confusing, although it can be mastered with a few pointers. Most important, the driver is the entire circuit, minus the LEDs. A driver IC is one or more ICs dedicated to controlling the current, and sometimes also the voltage, in the driver circuit. Fig. 2 shows an example of each. Nearly every LED-based light has a driver, even a simple one, but not every driver has a driver IC.

2. Complex, unique, dynamic design

Driver design is not simple and standardized as many people assume. First, LEDs require constant, high-current sources, which are unusual in electronics and create unusual challenges for product engineers. Moreover, the designs are complex and unique to every LED product. The end-product features are constantly evolving: from keypads to touch-screens, from one type of edge-lighting to another, and so forth. And, there is a wide variety of supply arrangements that obscure the landscape for observers: from conventional suppliers to contract manufacturers to widespread use of chip foundries to manufacturers of custom ICs for specialized driver designs.

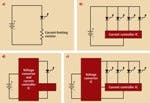

Controlling the input rail voltage is normally considered the task of the system’s power supply, but many LED applications require a voltage conversion to match the LED load. An IC may be dedicated for that purpose (Fig. 4c). For example, LED backlights can operate with strings of up to 10 or more LEDs in series, with a total string voltage of 60V or more.

3. IC integration and customization

Voltage conversion creates another option: the converter IC may be combined with a current-regulating function on the same chip (Fig. 4d). The choice to integrate voltage conversion and current regulation depends on many factors, such as the need for reduced component count, current requirements, and so forth.

The trend toward integration also offers an opportunity for chipmakers that use BCD (bipolar-CMOS-DMOS) processes to fabricate LED driver ICs that enable high-voltage operation. BCD allows for integration of diverse circuit elements – such as low-voltage analog and high-voltage power transistors – on the same chip. It is a high-margin growth opportunity for the foundries and chip suppliers that can do it.

Customers must also choose between custom ASICs (application-specific ICs) that form a perfect fit for their application versus off-the-shelf products that leverage non-recurring engineering costs. Customers commonly veer between custom and standard products depending on many changing demands in their product cycles.

4. Potentially disruptive AC-LEDs

Novel AC-LED products have the potential to complicate the driver market. In its purest form, the AC-LED eliminates the driver, using the diode features of the LED to replace conventional diodes. Other designs use some basic components to limit the current, but sparingly. If highly successful, the AC-LED could make some LED lighting products – such as replacement bulbs – more competitive and greatly expand the LED-lighting market. Such a move could be good for both the LED industry and the end users, but would displace potential driver sales for those products.

However, we expect that AC-LEDs will have an impact only in certain product segments. In replacement bulbs, the pressure to innovate is so high that the AC-LED is just one of several novel solutions, and there is no room for older, less-innovative designs. Consequently, there are plenty of opportunities for everyone.

The high-voltage LED (HV-LED) is another buzz word but it will have minimal impact on the driver market. LED-based products commonly use long strings of LEDs in series. Until recently, the LEDs have been packaged in discrete packages and assembled together in the luminaire or lamp. An HV-LED integrates the LED string onto the same chip or within the same package, gaining some advantages for the customer. It means little to the driver design, other than the usual considerations for the LED load that impacts every product design.

5. Volatile pricing

Estimates for IC pricing also complicate the forecast. It’s obvious that IC prices decline over time as volumes increase and margins shrink. What’s not as clear is the effect on the average price of changes in the product mix. New products can appear at much higher prices than more-mature products in the same category, but can earn the difference via savings in component count or improved LED performance. The new products may be priced higher because they use a larger chip that takes up more wafer area, because they use a more expensive foundry process, or simply because they deliver more value, and can earn greater margin for the chip supplier.

Temporary oversupply or shortages of products within the supply chain – such as driver ICs, LEDs, or the end products – also create fluctuations in prices. We ignore these short-term fluctuations; in our studies we focus on the underlying medium-term trends in demand and technology.

LEDs are relatively uniform and easy to understand – compared to drivers. As one supplier said, explaining drivers requires a deep dive, but few customers have the patience or expertise to listen for very long. Yet, with some patience, LED drivers can be appreciated as a critical partner to LEDs, which garner so much attention.