Vineyards and grain farms can scan grapes and cereals with an infrared LED-equipped smartphone to analyze food, water, and sugar content, using spectroscopy.

Osram has upped its game in the agricultural LED market, adding another near-infrared chip that reads the content of crops such as fruit or cereal to determine when they are ready for harvesting.

The new SFH 4736, part of Osram’s Oslon Black line, is designed to fit into a smartphone or tablet, and marks an improvement over Osram’s earlier SFH 4735 LED, which was positioned for the same horticultural niche.

Like the 4735 and other similar Osram chips, the new LED deploys near-infrared spectroscopy. In the case of the 4736, the technology scans a grain or fruit to ascertain the amount of sugar, water, and fat. Growers use this information to determine whether the crops are ready or whether they require more time before harvest.

Osram’s near-infrared spectroscopy chips shine infrared light on a subject and measures the light that reflects. By inference, the rest of the light has been absorbed in a manner that would be characteristic at certain levels of sugar, water, fat, and other substances.

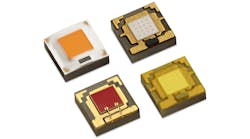

Amber waves of spectroscopy, using Osram’s SFH 4736 infrared LED for an agricultural test and measurement application. (Photo credit: Osram.)

Using the readings of the reflected light, a database helps the smartphone or tablet to analyze the makeup of the crop at any given time.Osram said an inherent lens in the new 4736 focuses much more light on the subject than did the 4735, which required separate optics. Thus, the 4736 LED receives much more reflected light to measure.

“Compared to SFH 4735 without a lens, we are achieving more than twice the output with the SFH 4736 in a solid angle of 80°,” said Carola Diez, senior marketing manager at Osram’s Osram Opto Semiconductors group.

Osram’s near-infrared spectroscopy chips shine a blue emitter through a phosphor coating, which converts the wavelength into a range between 650 and 1050 nm, which roughly corresponds to the near-infrared portion of light’s infrared spectrum. Near-infrared has shorter wavelengths than those in the short-wavelength, mid-wavelength, long-wavelength, and far-infrared segments of infrared. All of them have wavelengths too long to be visible to the human eye, which tops out at red.

Like other LED companies, Munich-based Osram has identified agricultural and horticultural applications as a key market for LEDs, so much so that it is the one market in which Osram plans to continue to offer luminaires — the company is otherwise exiting the luminaire market.

The SFH 4736 LED chip marks the latest in what has been a flurry of new Osram near-infrared chips this year, for various uses including horticulture and many others.

In September, it introduced the Synios SFH 4776, positioned to help consumers identify contents of apples and other foodstuff.

In July, with security cameras in mind, it added the SFH 4718A to its Oslon Black line.

That came a few months after it added six new models to the Oslon Black family for use in interior and exterior automotive applications. And in February, it introduced a 940-nm near-infrared chip that assists in facial recognition systems to unlock laptops, phones, and other electronic devices.

The company is building a strong portfolio of light-emitting chips as it seeks new digital markets. In addition to LEDs, the buildup includes VCSEL chips, an area in which Royal Philips has maintained a strong interest despite shedding LEDs and general lighting.

MARK HALPERis a contributing editor for LEDs Magazine, and an energy, technology, and business journalist ([email protected]).