This article was published in the March 2012 issue of LEDs Magazine.

View the Table of Contents and download the PDF file of the complete March 2012 issue, or view the E-zine version in your browser.

+++++

A diverse set of speakers ranging from lighting designers to research scientists to executives from LED and lighting manufacturers took the stage in the “LEDs in Lighting” track at Strategies in Light. The central theme was obstacles to broader deployment of solid-state lighting (SSL) and potential solutions that can drive such deployment. The track included success stories as well, but the overriding theme was unmistakably focused on how LEDs can eventually dominate the general-lighting market.

Ferreira discussed some of the challenges that still stand in the way of broader adoption of LED lighting. He asked the audience to remember the number sequence 15, 3, 15. The first two numbers represent the life expectancy, in years, of LED and CFL lamps respectively, based on 9 hours of operation per day. The third number represents the average time, in years, that a person lives in the same home. Ferreira said, “Most LED bulbs will outlast the average US homeowner.”

Residential obstacles

The point that Ferreira was making is that buying an LED lamp remains an unlikely choice for the typical consumer. He said that a high-quality 60W-equivalent CFL lamp costs a little more than $5 today, while the Philips EnduraLED 60W-equivalent lamp costs around $32. Ferreira said that the return on investment (ROI) of the two lamps is similar but the ROI calculation for LEDs is based on their much longer life. “Most people don’t make a [buying] decision based on a 15-year lifespan with the possible exception of their home,” he said.

An energy-efficiency theme pervaded Ferreira’s talk, but he clearly believes that the LED lighting industry must do more than cut energy use to fully succeed. He discussed what he called the “five simple steps” that can accelerate the adoption of SSL in both the consumer and professional markets: always innovate; tell the story; create an audience; establish rules; and start early.

Innovation was a widely-used word at SIL and Ferreira, among others, suggested rethinking lighting products. He stressed that there is nothing sacred about the socket and used a table task lamp with an integrated LED light engine and driver as an example.

But Ferreira was disappointed in an exchange he overheard while visiting the display. A visitor asked a garden volunteer about the lighting, and the volunteer said, “I don’t exactly know how it works. I think they are using colored party bulbs.” The project could not have been realized without efficient RGB LEDs and Ferreira said, “I would describe that as a missed opportunity” meaning a chance to educate public on LED technology.

Retail theater

Ferreira used new LED lighting in a Starbucks store in New York City’s Times Square as an example of creating an audience. LED Source supplied the LED lighting products and Focus Lighting handled the lighting design and used the surrounding theater district as a theme (Fig. 2). Ferreira said, “It’s almost like Broadway. It’s retail theater. It can be a poster child for LED success.” Such retrofits are part of Starbuck’s goal to reduce energy use by 25% by 2015 across 17,000 stores. But Ferreira’s point is that such projects will win the hearts of the public in terms of recognizing the potential of SSL and driving adoption.

Rules are needed to ensure SSL success according to Ferreira. He didn’t mention the new US Department of Energy (DOE) lamp-efficiency guidelines, but suggested that the government should provide incentives such as tax breaks for the SSL industry. He said rules are key to ensuring that the lighting industry doesn’t go backwards.

Finally Ferreira suggested that we should start early in educating our children about good energy habits. He said children are open to technology and innovation and aren’t intimidated by technology such as lighting control systems and smartphone-like apps. For lighting companies, Ferreira said the choices are simple – “innovate or perish.”

CRI and CCT

A number of presentations in the LEDs in Lighting track focused on color quality, and the hurdles that still face the industry in that area. Jean Paul Freyssinier, research scientist at the Lighting Research Center (LRC) at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, targeted both measures of color rendering and color temperature in his presentation entitled “Class A lighting.”

Focusing specifically on color rendering, Freyssinier said that the lighting industry now accepts that “no single metric can characterize color rendering.” He said that there are too many dimensions to color rendering – including color fidelity, saturation, and discrimination of hues – to capture in a single metric ().

Whether Freyssinier is right about an industry-wide opinion on color rendering or not, he used the SIL platform to advocate the LRC’s gamut area index (GAI) metric that is meant to be used in combination with CRI. Freyssinier said that people prefer a light source that enhances color without distortion or making the object look unnatural. And he said that light sources with high CRI and GAI will consistently outperform light sources that rate high in only one of these two metrics.

Chromaticity variances

The bulk of Freyssinier's presentation, however, was focused on CCT and perhaps a misguided perception of the accepted definition of a white light source. Freyssinier said, “By definition CCT is a line in the color space, not a single point.” Two light sources can have the same CCT and still be quite different in terms of chromaticity in the CIE 1931 color space.

The industry widely accepts that the black-body locus that’s plotted in the color space represents a white source at varying CCT values. But the LRC performed a study to seek the answer to Freyssinier’s question, “Is there a difference in terms of perception or preference for end users?”

The testers were asked to respond immediately after seeing each light source and after an adaption period of 45 seconds. The testers judged the hue of the light source responding to whether they perceived the source to be green/yellow in nature or purple/violet. The testers were also asked to rate the hue relative to their perception of pure white.

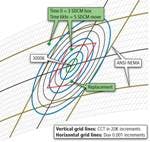

The details of the research are lengthy in nature, but Fig. 3 shows a surprising result. Only at around 4100K did the perception of the testers align with the black-body locus. At cooler CCTs the testers preferred chromaticity slightly above the locus. More importantly, at warmer CCTs the testers preferred chromaticity significantly below the locus.

Chromaticity white points

At 2700K, Freyssinier said that the difference in terms of perception between the black-body locus and the preferred white point is equal to a 13-15-step MacAdam ellipse (also referred to as a SDCM or standard deviation of color matching ellipse). Freyssinier said that the difference in terms of perception between the black-body locus and the preferred white point at 2700K is greater than the perceived difference between the three white points at 3500K, 3000K, and 2700K despite the fact that those white points are more spread out on the color-space graph.

Closing the loop around color rendering, CCT, and chromaticity, Freyssinier addressed the title of his presentation. He defines a Class A light source as one that has CRI above 80, GAI between 80 and 100, and chromaticity located along the white line in the color space identified by the LRC’s study.

Ron Steen, VP business development at Xicato, also addressed color quality and focused on the lack of standards that specify color deviation and the problem of changes in color over time of LED sources. Steen said that SSL deployment is happening, but not as quickly as some industry proponents believe it should. He said that the LED industry focus has been on efficacy and that great progress has been made in that area. But he asked, “With 150 lm/W, why isn’t [mass adoption of SSL] happening?” Steen answered saying “Maybe one of the reasons it hasn’t happened is because it’s ugly.”

Color variance

Steen used a screen to project light with different characteristics to demonstrate the potential problems that the LED industry still faces in terms of color consistency. First he compared two 3000K sources side by side that were within the 7-step SDCM bounds of the ANSI binning scheme for LEDs. The lights had only a 19K difference in CCT. The difference was noticeable but perhaps not unacceptable. He then showed two sources that fell within a 4-step SDCM ellipse. But in this case he used sources that were 39K apart albeit much closer in chromaticity. The difference was significant and Steen concluded that it would be problematic in most lighting applications. He said that the industry needs LEDs that are within a 1-step SDCM ellipse in terms of chromaticity and a 2-step SDCM ellipse in terms of CCT.

Steen also demonstrated issues with CRI using a saturated red color patch and light sources with different spectral power distributions. Color rendering is one area in which he laments the lack of a usable standard. Differing with Freyssinier, Steen spoke positively about color quality scale (CQS) as an accurate metric. Steen said “I hope the industry actually adopts it so that we can try to get down to one metric.”

Still, Steen’s larger concern is the need for standards that define color shift over time (and obviously LEDs that would meet such standards). He said, “It might not be lumen depreciation that defines lifetime of LEDs. It may indeed be color that defines the lifetime of a source.”

The LM-80 standard used to specify LED lifetime does not really address color, said Steen. It does require an LED maker to disclose color shift over 6000 hours, but doesn’t set limits on acceptable shift. Steen said that Energy Star requires luminaires to maintain color within a range of 0.007 relative to the CIE 1976 color space. But that delta, according to Steen, is in the range of a 7-step SDCM ellipse. CELMA has even less rigorous guidelines in Europe.

Accepted quality levels

Steen understands the difficulty faced by the standards bodies. He said “Statisticians do not know how to statistically extrapolate color movement over time.” Steen said the industry has mistakenly accepted that color consistency is assured by LEDs that fall within a 3-step SDCM ellipse out of the box, and in the worst case, those LEDs should shift a maximum of 5 additional steps over time. In general the industry is managing to live with such performance, in part according to Steen because all of the LEDs in an installation typically shift in the same direction over time.

As a solution, Steen proposed a color-maintenance curve that is modeled after the commonly used lumen-maintenance curve and specs such as hours to L70. He proposed holding LED color maintenance to the 1-step chromaticity and 2-step CCT limits that he discussed earlier.

Modular products

Getting back to the subject of innovation, a number of SIL speakers lauded the fact that LEDs will free product designers from accepted lighting form factors including linear troffers, downlights, and even bulbs. Still, we haven’t yet witnessed a lot of innovation in form factor. Ironically a company called Nualight, which is focused on retail lighting for food displays, was the lone company that addressed the need for customizable form in the LEDs in Lighting track.

Vincent Guenebaut, head of product innovation at Nualight, said “We are not limited anymore by the size and shape of fluorescent tubes.” Instead Nualight is taking a modular approach by offering configurable SSL systems that can fit in refrigerated display cases and above display counters that hold items such as produce. Guenebaut said, “The luminaire becomes the main attribute of a case.”

While Nualight does offer modular products, Guenebaut said the company’s approach to product design is to define interfaces rather than modules. The description sounds much like the approach of the Zhaga consortium. The interfaces are mechanical, thermal and electrical, and ultimately allow LED modules to be packaged in custom forms.

Guenebaut warned that the approach has risk in that you can end up with too many modules if you are not careful. He also said that modules can in some cases lead to compromises in terms of performance relative to a luminaire designed specifically for an application. But there are positives as well. Guenebaut said that because its modules are used across many different products, the company can spend more time and effort optimizing the performance in terms of parameters such as efficacy.

Success stories

There were other SSL success stories were also discussed in the lighting track. Michael Royer, lighting engineer at the DOE’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL), presented results from the lab’s latest round of tests of LED-based retrofit lamps. The results were much improved over the prior round especially in the case of A-lamps with most delivering efficacy in the 60 lm/W range and CRI around 80.

Sarena McComas and Jennifer Rueth, partners at lighting design firm Type A Productions, presented a case study of an LED lighting project at the JW Marriott hotel in Indianapolis, Indiana. The project included the installation of more than 5000 LED downlights, mostly in guest rooms. The result has been 25-30% energy savings over what legacy sources would have required, and a similar reduction in the size of emergency generators required.

The project faced numerous obstacles including issues with contractors that were hesitant about SSL, and with lighting manufacturers' representatives that failed to produce a suitable product. Ultimately the team found a single downlight that met their requirements including a relatively-tight mounting space.

When asked, McComas said that the chosen downlight had a CCT of 3000K and a CRI of 79. But McComas said, “CRI has nothing to do with LEDs. It’s not a valuable metric. It doesn’t even work for incandescent.” Apparently the team couldn’t correlate CRI scores with light that looked good in the application.

Museum lighting

Naomi Miller, senior lighting engineer with PNNL, presented a number of examples of LED lighting in museums. One reason that LED lighting is attractive to museums is that SSL does not emit energy in the IR or UV bands – and both are known as harmful. But Miller said that is a misconception that only UV and IR damage art. She said that paintings can fade due to exposure to visible light as well, and that some energy bands are especially damaging. There is the potential with LEDs to precisely control the spectral power distribution.

Several speakers in the track discussed controls including Redwood Systems – a company that specializes in networked lighting for office spaces. Redwood chief marketing officer Sam Klepper covered the familiar ground of saving energy via dimming lights and turning lights off based on occupancy sensors. And he described other benefits of having occupancy sensors throughout an office. He said Redwood customers are using the lighting system to detect the availably of conference rooms dynamically and even to enhance security by detecting the presence of people in areas that should be unoccupied.

The lone speaker from an LED manufacturer was Mark McClear, global director of applications engineering at Cree. McClear insisted that the best is yet to come in LEDs. He described Cree’s newest products, the XLamp XT-E family (Fig. 6), as a “third-generation” LED (www.ledsmagazine.com/news/9/2/7). He said second-generation LEDs are “running out of gas” in terms of efficacy gains, but that the third-generation designs will get the industry to 200 lm/W. He expects Cree and other makers of lighting-class LEDs such as Nichia, Philips Lumileds, and Osram Opto Semiconductors to all deliver third-generation families soon and said Cree was already in high volume already with its newest LEDs.

McClear clearly sees LEDs as the primary source for general lighting going forward. He addressed OLED lighting and the fact that some projections have OLEDs achieving fluorescent-T8 efficacy and brightness levels by 2017. But he said that in 2017, OLED will be competing with LEDs as the incumbent technology rather than with T8s. He said, “Can OLED enter that market and compete? I think no.”

LED droop – the unexplained drop in efficacy at higher drive currents – was also a target in McClear’s presentation, and has been considered an obstacle to broader SSL deployment. While droop hasn’t been solved, McClear believes efficacy gains in general have eliminated droop as a concern. He said that at 50 lm/W droop was a big concern, but with LED component efficacy over 100 lm/W droop is a hurdle that has been cleared.