This article was published in the July/August 2012 issue of LEDs Magazine.

View the Table of Contents and download the PDF file of the complete July/August 2012 issue, or view the E-zine version in your browser.

+++++

In April 2012, Intematix unveiled its new ChromaLit XT remote-phosphor lighting solution. This optic design integrates innovative remote-phosphor technology to produce a material that can withstand temperatures of up to 270°C, and can increase LED system efficiency by up to 30%.

The importance of Intematix’s new product and other remote-phosphor innovations cannot be ignored. After all, remote phosphor addresses a fundamental pain point in the solid-state lighting industry and the one main barrier to widespread adoption of LEDs: cost, cost, cost. But intellectual property concerns cloud the picture for remote-phosphor usage.

Market potential

Even the most optimistic forecasts of the LED industry demand dramatic improvements in LED efficiency and price. A US Department of Energy (DOE) report published in January 2012 predicted that LEDs will occupy up to 73.7% of all lighting applications in the United States by 2030, and consequently drive down the energy costs of lighting by 46%. These DOE estimates, however, require a more than 100% increase in LED efficacy (measured by lumens per watt), a 50-200% increase in bulb longevity, and an 18-fold decrease in price over the same time span.

Cost advantages of remote phosphor

Generally, to produce the broad-spectrum white light that we love, LED manufacturers use one of two different methods: mixing differently colored LEDs, or depositing a yellow phosphor layer on a royal-blue LED die to convert the wavelength of the light. Unfortunately, these processes are highly inefficient. Mixing multiple LED colors requires costly inventory processes. Depositing a phosphor layer for each LED die causes inconsistency in LED color temperature (CCT) and color rendering (CRI), as a phosphor layer will degrade over time due to the heat of the LED die.

More importantly, remote phosphors streamline the entire LED manufacturing and inventory process. Currently, companies stock LEDs that produce blue light across multiple wavelengths, in order to produce white light of different color temperatures and quality. With remote phosphor, companies can stock fewer blue wavelengths and target specific CCTs and CRI by replacing the remote-phosphor substrate.

Battle Royale?

Given the potential size of the LED lighting market, and the revolutionary nature of remote phosphors to the industry, a battle already rages on for ownership of the fundamental technology behind remote phosphors. Our analysis will focus on two of the biggest players in the field: Cree and Intematix.

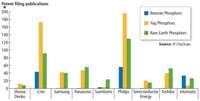

Philips also has a strong portfolio in remote phosphors and engages in market competition with Cree and Intematix (Fig. 2). However, Philips already has access to Cree’s remote-phosphor patents through a cross-license agreement in 2010, and so will not be the focus of our analysis.

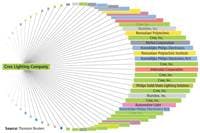

Cree

Just this past fall, Cree launched a licensing program for its remote-phosphor technology, a move that positions the company as both an advocate of remote-phosphor technology and an enforcer of its IP ownership rights. George Brandes, Cree’s director of intellectual property licensing, said: “If you want to make a white light with a blue LED and a phosphor, you probably want to have access to Cree patents... we feel that they are fundamental to making a remote-phosphor luminaire.” So far, Aurora Energie, Horner, Ledzworld Technology, Vexica Technology, and Wyndsor Lighting have signed up for Cree’s licensing program.

Cree’s first issued patent in the remote-phosphor space (US 6,3500,41 B1 entitled “High output radial dispersing lamp using a solid state light source”) is cited by 167 patents, including a patent by Intematix. The high number of citations suggests that other experts in the field consider this patent to represent fundamental technology in the space. The early priority date (December 1999) of US 6,350,041 in relation to the rest of Cree’s portfolio also suggests the importance of this innovation, as patents with an earlier priority date can serve as prior art to subsequent patents and affect their validity.

Intematix

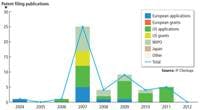

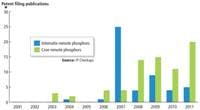

Despite Cree’s position on remote-phosphor licensing, Intematix has charted its own course in remote-phosphor technology and has yet to take a license from Cree. Intematix, a phosphor technology company based in Fremont, California, has 31 remote-phosphor patent applications across Europe, Japan, and the United States, and 13 more international patent applications (Fig. 4). Most importantly, Intematix has 5 issued patents in the United States, but none abroad.

Unlike Cree, Intematix has decided on a full disclosure policy for its remote-phosphor patents. The Intematix website lists a selection of its remote-phosphor patents, and the de-duplicated portfolio of published patents is shown in Table 2.

Intematix’s 2012 ChromaLit brochure mentions that the Intematix remote-phosphor portfolio is 56 patents strong, suggesting that the company has filed more patents within the last 18 months that are yet to be published.

Light at the end of the tunnel

Both Intematix and Cree have strong positions in the remote-phosphor space. Cree has a larger patent portfolio than Intematix and earlier priority dates for some of its key patents, but the IP system will still protect Intematix’s technological improvements as long as they are novel and non-obvious.

Though the lawyers and courts may ultimately have to decide ownership of remote-phosphor technologies, this will not stop innovation. Cree and Intematix still have plenty of room to develop their next new products, increase LED efficiency and longevity, and decrease LED prices for broad market adoption.

Regardless of how the patent battles play out, the competition between Intematix and Cree is a boon for the LED industry as a whole. In the on-going fight for technological dominance, LED companies will have the incentive to innovate and winnow down costs far enough to establish a deeper presence in markets that still have enormous growth potential.